Last night I cycled back from Westminster to East London and just as I got over the Old Street roundabout I felt an increasingly familiar sense of ‘Nearly home’. As I turned into London Fields, Hackney, I smiled. This is my place.

What does that mean? What is Kith?

I have spent countless hours in the last twelve years walking its boundaries. I can guarantee I know a few people around. I know the shape of the trees and what species they are. I know where the muddy bits are, where you can pick cherries in season and where to go to get a free bit of flapjack… This is my neighbourhood. My ‘hood.

Where is your ‘hood? And as a child how far did it stretch? That is your kith. And it is important.

Jay Griffiths tells us ‘kith’ (as in ‘kith and kin’) is from the Old English meaning one’s native country, the home outside the house, the immediate locale, the first landscape we know as children, the place we love[1].

This certainly doesn’t have to be a babbling brook or some field of daffodils. My ‘Amor Loci’[2] at the age of seven was a bit of waste ground at the bottom of our street on a Liverpool housing estate. There the weeds grew high enough in summer to tie together into dens and noisy games could be held without being shouted at by neighbours. By the age of 9 my kith had expanded to cover the whole estate, and by 10 or 11 it stretched a mile to the swimming pool.

Why am I relating these oh so personal stories?

Because this is what children and young people are losing fast. Have in fact largely lost in the last two generations.

Mayer Hillman started to research independent mobility in 1971 when only 50% of seven year olds were allowed to walk by themselves to the local shop, park or school[3]. Now it is less than 10%. In the parts of London I live in I guarantee it is less than that.

Without that walking around, and critically the dawdling and doodling, the side trips to see if the tree has grown a bit, the jumps in puddles and the running past the slightly scary house, how do children today build THEIR kith? Their Amor Loci? And in losing it, do we understand what they have lost?

Jay Griffiths writes that:

“Kith kindles the kinship which children so easily feel for the natural world and without that kinship, nature loses out, bereft of the children who grow up to protect it.”[4]

In a world of floods and climate change, larch disease and species depredation that is critically important. But, I would like you to consider, it is not the only fall out.

Where I live I see everyday what happens when young people have no ownership of their area – litter, broken bottles, dumped bikes. And that’s the twenty somethings that have just moved in and will be off again when they realise working in a coffee bar won’t pay London Fields rents.

For children the impact can be subtle but far more insidious. They may not feel safe. They may not feel they belong. They may not feel trusted. And that affects their self-esteem, self-confidence and self-regulation. These are not the ‘at risk’ children. These are, I suggest, to a greater or lesser extent the majority.

I’m undertaking research now looking at some of the potential health implications for children that have had little opportunity to play out, and it really worries me[5]. It should worry us all. What do we see on the rise in the last 40 years as children’s freedom to roam has diminished? Obesity and lack of physical activity is the obvious fall out, but we should arguably also be looking at gang culture, sexually transmitted infections, understanding of ‘consent’, self harming, smoking. There is little direct research correlating lack of outdoors time with these more destructive activities, but the more I read the more I’m seeing the potential links with poor self-regulation, with not feeling safe in a place.

I’d love to know what you think.

CYPN reported recently that David Cameron has announced funding for parenting classes[6]. He even (wow!!!) mentioned the ‘play’ word. Leaving aside any other immediate reactions[7], what chance that part of these parenting classes will be run outdoors? Or will include an emphasis that parents should trust their seven year olds – and their neighbours – a little more if they want their children to grow up grounded?

I moved house at 12, and from then until twelve years ago I moved every couple of years or so and I forgot what ‘kith’, ‘amor loci’, really felt like[8]. Now I’ve remembered again I realise how precious that grounding is. It gives me strength and makes me want to protect where I live and the wider environment because of it. Maybe next time you smile as you turn into your street, you could take a second to think how we can make sure the children around you are doing so too?

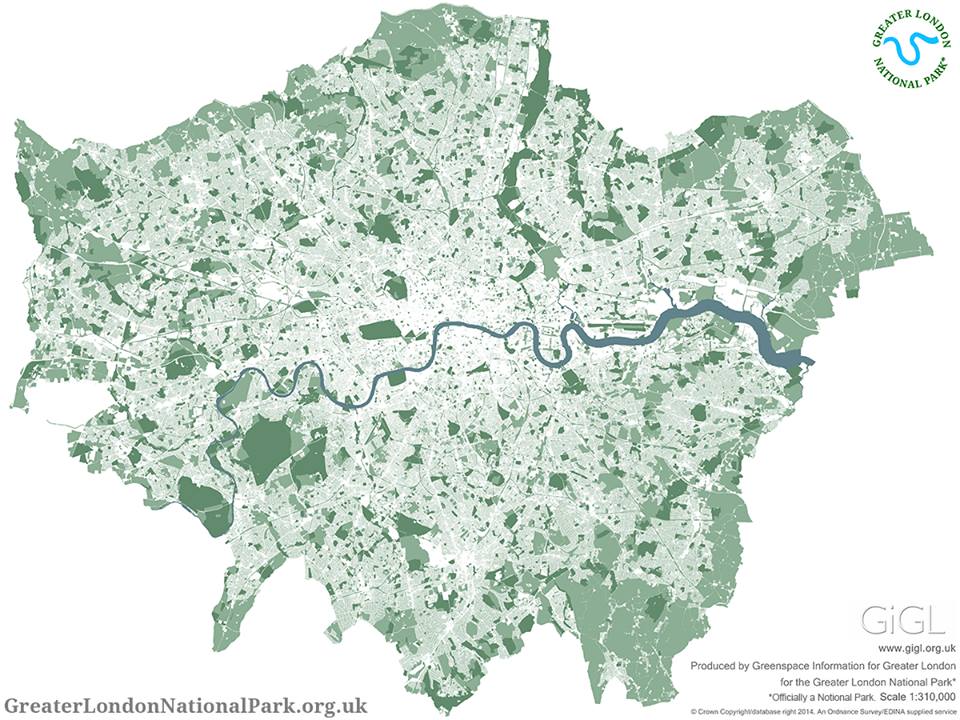

If you have any related anecdotes, projects that are working to rewild children in your neighbourhoods or a story to tell about your own ‘kith’, I’d love to hear it. Please also take a moment to check out the The Wild Network and the Greater London National Park as they seek to bring together all the people responsible – including you, the children and youth sectors – to help children play and travel outdoors independently once more.  [9]

[9]

[1] Kith: The Riddle of the Childscape, by Jay Griffiths, 2013 http://www.jaygriffiths.com

[2] beloved location – from W.H. Auden as described by Jay Griffiths

[3] http://www.psi.org.uk/site/news_article/851

[4] P5, Kith, Jay Griffiths. 2013

[5] Dangerous Play – http://outdoorpeople.org.uk/project-type/dangerous-play/

[6] http://www.cypnow.co.uk/cyp/news/1155484/cameron-announces-drive-to-improve-parenting-skills

[7] Children’s Centres?!?!?

[8] Mum, please note I got lots and lots of good things from all that moving around too!

[9] I hope all the footnotes are helpful rather than distracting. I’m both reading lots of academic articles and also rereading Terry Pratchett’s Discworld books, so footnotes rather than lots of in-text hyperlinks feels right…