In 2019, thanks to a five-year campaign, London is set to become a National Park City. This would afford the nation’s capital similar similar status to treasured national areas such as the Lake District, Snowdonia or the Norfolk Broads – and get London’s kids more connected to nature.

Utopian dreams of the city have often taken the form of a Grand Plan. From Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City Movement to the Liuzhou Forest City conceived by Stefano Boeri Architetti many urban planners dream of creating an Urban Eden, where high-density development co-exists with cultivated or semi-wild natural spaces (in Garden Cities each householder had a fruit tree planted in their front garden so they could enjoy the produce).

The concept of London as the world’s first National Park City is potentially as radical as any of these ideas. It has the same visionary edge, but what sets the idea apart is its roots-up, rather than top-down, approach.

Although administered by a central authority, the power of National Park status is more about harnessing the resources that already exist, using these to create a shift in the public imagination, rather than spending vast sums of money on infrastructure projects.

The idea was the brainchild of Dan Raven-Ellison, former teacher turned ‘guerrilla geographer’. The campaign has made astonishing progress – just over four years from inception to potential realisation, gaining support along the way from the public, politicians and a host of partner organisations (including Outdoor People – Director Cath has been a member of the Advisory Board from the outset).

What may have seemed like a wild idea at the start, has in part, succeeded because it’s not nearly as far-fetched as it first appears. While we are used to talking about London in terms of the man-made – skyscrapers, congestion, fumes, development – Raven-Ellison points out that we habitually overlook the other reality of London, a rich ecological patchwork of diverse habitats.

“There are nearly as many trees as people in London and we share the capital with 14,000 other species. 49.5% of London is already made up of the city’s 3.8 million gardens, 3,000 parks, canals, rivers, ponds and nature reserves. One of our aims … is to make more than half of the capital physically green and blue.’’

London’s green spaces include both the wide open expanses of former Royal Hunting grounds – Richmond, Epping, and Hyde Park and a myriad of little patches, corridors and squares of green, which exist in even the most dense urban areas. The National Park concept involves facilitating local and human-scale development, connecting spaces with people, and in the process encouraging everyone to change the way they think about their locality, for example, by persuading schools to plant species that encourage eco-diversity.

Encouraging the development of these micro areas – threaded together by green corridors, and bolstered by an overarching vision – could prove transformative, says Raven Ellison: ‘If every Londoner made just 1 square metre green, we’d collectively make the majority of the city green and blue.’.

The vision is eminently achievable – In its European Green City Index of 2009, Siemens rated London 11th out of 32 major cities across the continent. In a more recent assessment conducted by Arcadis, which assessed major cities across the globe in terms of their sustainability, London again sat in the top 10, rated poorly for many important aspects such as air quality, but on a par with Copenhagen for Greenhouse Gas emissions. Not exactly a picture of Eden, but neither the concrete and glass behemoth that has become fixed in our collective imagination.

The impact of the initiative goes beyond a physical and imaginative transformation. The National Park ethos commits to developing social, economic and health benefits too. As Raven-Ellison points out: ‘It’s been estimated that our public parks save the NHS nearly £1 billion a year in health costs, including £370 million as a result of better mental health.’

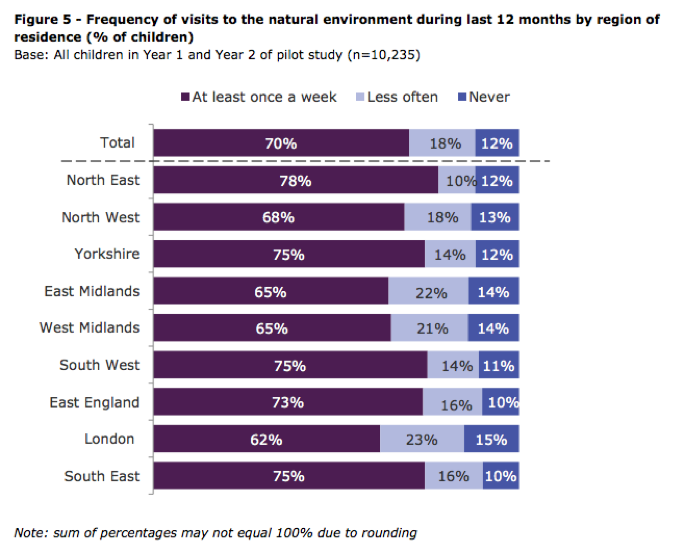

Perhaps the most exciting is the prospect of using London’s green spaces as an intensive resource for play, learning and enjoyment, both for formal and informal learning. In the latest ‘Monitoring Engagement with the Natural Environment‘ (MENE 2015-16) report it shows that across the UK 48% of visits to parks are with dogs, but only 10% with children [pdf link] . Whilst we love our dogs, couldn’t the children get as many green space visits? In London we know visits to green spaces are even less than in the rest of the country – in the laste MENE report on children [pdf link] 38% of London’s children visited a green space – a park, gardens, beach or countryside – less than once a week and 15% – 1 in 7 – NEVER go.

It was partly that disconnect with nature that sparked this campaign in the first place.

Cath Prisk, Founder of Outdoor People, is particularly concerned about this issue: “If we want children to care about the planet, love where they live and have freedom to play, then we need to start with finding ways for London families to simply get outdoors and enjoy the gorgeous green spaces around them. Hackney alone has 56 public parks and gardens – that’s more than one free place to visit every single week!”

Conan Doyle once described the sight of London’s Boarding Schools, seen from the vantage point of a railway line as ’brick islands in a lead-coloured sea.’ It may be that in a decade or so people will look down and see open spaces in a patchwork of green as an essential aspect of a citizen’s route to learning and recreation. National Park Authorities have a duty to ‘conserve and enhance the natural beauty, wildlife and cultural heritage, and promote opportunities for the understanding and enjoyment of the special qualities of national parks by the public.’

The plan for London includes a specific aim to connect all children with the natural environment, and in particular the 1 in 7 children who never visit a green space. This gives strength to existing initiatives such as Forest Schools and projects such as Outdoor People’s Wild Walks.

Likewise, there are potential economic benefits., Richard Florida contended that global cities attain their status because of their cultural magnetism: because they are free-spirited, energetic, creative, because they are desirable places to live. It is not at all perverse to claim that National Park City status will ensure that London retains its competitive edge in the economic field, because of the huge improvement it will make to the quality of life for every citizen.

Moreover, with the rapid approach of Brexit, a strategic commitment such as the National City Park could prove to be a bulwark against any rowback on high environmental and social standards encouraged by the European Union, particularly as National Park Authorities have a duty to foster the economic and social well-being of local communities within the park’s boundaries.

The National Park City initiative offers a unifying vision, and could act as a template for other areas in the UK to follow. The Seven Lochs project in Glasgow may have a similar impact, as could the creation of the Great Northern Forest, an idea put forward by the government in recent weeks. All of these schemes promise an even greater connection between local populations and their environment Raven Ellison believes that it is by harnessing people’s energy and enthusiasm that the idea will come to life: ‘The capital can become a National Park City because Londoners have been creating, protecting, improving and enjoying green and public spaces for hundreds of years.’